“The Eyes Have It” Fatima Ronquillo and the Delights of Imaginary Portraiture

by Huntley Dent, catalog essay for “FATIMA RONQUILLO Recollected: Portraits of Enchantment” exhibition

Millicent Rogers Museum, Taos, New Mexico June – September 2023

Portrait painters are bound by a strict rule that is almost a law. Call it the Law of Likeness, the obligation to paint a realistic image. Subjects of portraits expect to recognize themselves, and ever since the advent of photography, verisimilitude has become even stricter. “That doesn’t even look like me” is a judgment to be dreaded.

A stroll through this exhibit of paintings by Fatima Ronquillo reveals at a glance that she is lawless in the most delightful way. She isn’t bound by the Law of Likeness, because her genre is imaginary portraiture. The people she depicts have never existed except in her imagination. Her portraits have a strong personal bent—she has created an extended family who share the same genes, artistically speaking. They are pleasant to look at and in turn are eager to please. They are flesh and blood only to a degree—rounded, childlike faces with rosebud lips predominate, idealized to the point that angles and bones, spots and blemishes, much less the ravages of age, have been imagined away.

“Like,” the root word of likeness, has another meaning, and Ronquillo’s extended family are unquestionably likable. If they didn’t possess a certain reserve, they’d be tempted to reach out for an affectionate embrace. You’d never suspect them of guile or secrecy. Yet they have both, which is why Ronquillo’s art has a teasing quality—she provides clues to her subjects’ other life, a dimension beneath the skin.

A fruitful way to peel back this hidden dimension is through the eyes in her portraits. Ronquillo doesn’t traffic in the romantic notion of eyes as the window to the soul. Some of her eyes are as unreadable as china dolls. It is mysterious how these portraits hold your gaze when the gaze they return is constructed purely from artifice. Look closely, and you’ll notice that she typically doesn’t paint eyelashes, folded lids, or half-lidded eyes. Rembrandt, the most famous self-portraitist in art history, looked into a mirror and portrayed every aspect of human nature he saw in himself, and it is ineffably touching to watch his self-portraits as time brought tragedy, failure, insight, wisdom, resignation, and humility into his face, most especially his eyes.

The closest that Ronquillo has come to a self-portrait, on the other hand, isn’t recognizably about her unless you had personal knowledge. Titled “The Artist’s Eye and Hand with Jasmines and Sweet Peas,” this exquisite image, barely six inches square, distills three of her favorite motifs—eyes, hands, and flowers—in a quasi-collage. As idealized as Ronquillo’s faces are, she is obsessively detailed in her depiction of nature. Her extended family comes with a menagerie of birds and beasts that are arrayed in lifelike furs and feathers (sometimes scales and armor plating).

“The Artist’s Eye and Hand with Jasmines and Sweet Peas”

This gives a humorous, piquant air to a painting like “The Wanderers,” where a little boy seems perfectly content to be sitting astride a bison, and in turn, despite a glint of wariness in its eye, the animal is patient about having a rider. Ronquillo’s wildlife exist in a peaceable kingdom. She doesn’t force symbolism on the viewer, but there is always at least a hint of it everywhere. Here, the child is holding a peregrine falcon, and peregrination is the essence of wandering.

As a longtime resident of Santa Fe, Ronquillo often takes a local perspective on the naturalist side of her paintings. The sweet peas she lovingly details can be found growing wild on the banks of the Santa Fe River, and the presence of a Rocky Mountain goat, Gila monster, and jaguar is authentic. In one of her few religious paintings, it seems incongruous for a marmoset to be nestling in the arms of a nun, who also happens to be wearing a huge flower arrangement on her head. Ronquillo’s imagination crosses over into the dream world of Surrealism in such images.

“Man with Gila Monster”

Good painting asks for attentive viewers, and just as she uses a technique of layered glazes to achieve her luminous effects, Ronquillo layers in associations gleaned from a constant, detailed study of art history. The painting titled “Child with Armadillo and Golden-Cheeked Warbler” indicates how seamlessly she weaves her Surrealist motifs with naturalism and art history. The florid pink bow on the child’s head refers to a Goya painting, the jewel-like bird to an endangered species found only in the Texas hill country; the lavish embroidery on the costume is Elizabethan, and the girl herself recalls Ronquillo’s roots in the Philippines.

Another favorite motif is the pearl-encircled “lover’s eye,” a decorative device that became briefly popular in England around 1800. These eye miniatures, as they were also called, commemorated a loved one (perhaps a secret mistress?) or the deceased. The eyes, gazing at us without a face, are among the most evocative images in a gallery filled with memorable images.

As easy as it is to point out what we see in the paintings, I’m brought back to what we don’t see, the element of mystery and hidden meaning. There’s a “now you see me, now you don’t” aura when a few of these imaginary persons wear masks or eye patches that don’t disguise them at all, as if the intention is ambiguous about being seen, or known.

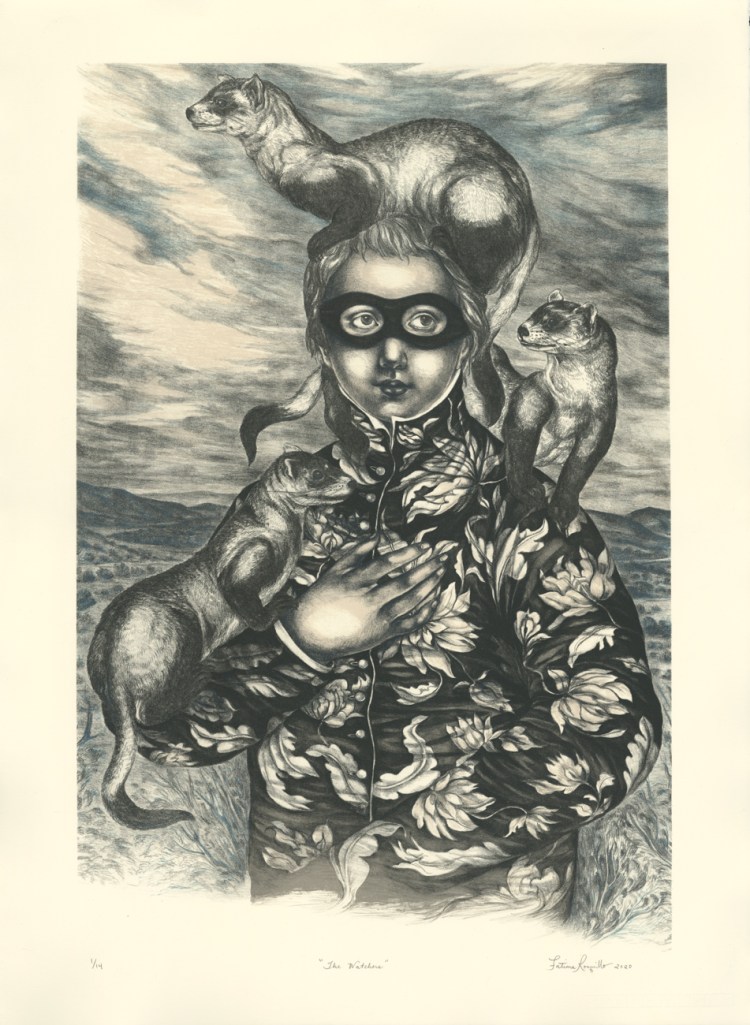

Ronquillo has only recently ventured into printmaking, and the two examples represented here stand as opposites. “The First Jasmines” is a subtle blend of five colors, rendered almost like a sketch, with personal associations going back to the Philippines in the child’s face. The child in the second print, “The Watchers,” is just as self-composed, but she wears a black bandido mask and is almost covered in black-footed ferrets, a furtively rare Western animal. The atmosphere is dark to the point of oppressiveness, yet the image is also too fantastic to be morose or menacing.

Everywhere in Ronquillo’s work the viewer is left to encroach into the mystery, or not, just as the fluid gender that typifies some faces can be recognized as he-she, or not. Her people don’t really care if they are boys or girls. The one thing they are certain about is that they live in an Eden where every creature is benign, flowers never fade, girls sprout dainty wings, and even the deadly coral snake lies gently in the palm of their hand.

Aether

“Devotion” by Rachel Haggerty Aether Magazine Issue 1, Fall/Winter 2011, pp. 16-19 view article

Immediately engaging, the work of Fatima Ronquillo reminds us of another time, one that may or may not exist. Painted in a similar manner to that of the European masters and using much of the same language as Early American Colonial art and Latin American art, each piece feels like a secret world revealed. Her symbolism is the only clue as to what lies beyond.

Born in the Philippines in 1976, Ronquillo moved with her family to San Antonio, Texas when she was 11. Finding herself friendless in a new country, Ronquillo sought refuge in the local libraries. The endless supply of books opened up imaginary places and characters into which she escaped. Studying the pages of art history and mimicking the masters, Ronquillo taught herself to draw and then to paint. Using flat planes and blocks of color, she began to formulate the symbolic language she uses today. Round faces with crescent eyes and latching stares appeared holding bowls of fruit and flowers. A young girl clutched a dove and simple pastoral landscapes eased into the backgrounds. Over the years, her technique tightened and her color choices became richer. Her artistic voice echoed many of the same notes as before, but it began to mature. Her symbolisim flourished into a fascinating visual language that hints at her characters’ intimate and mysterious worlds.

Ronquillo’s symbols have evolved from the passive to the active, inviting our curiosity and stimulating our imaginations. At first, flowers painted in a folk style appeared as offerings to the viewer. However, in recent paintings they appear as more of a possession. Wings that had once adorned her characters innocently now rest on coy and confident shoulders. The sweet monkey appears as a devious playmate. Her birds are no longer quiet bystanders, but messengers carrying promise of other lands. Her arrows point toward a mischievous and deliberate action. We are led to believe something or someone exists beyond the picture plane.

Ronquillo began incorporating literal depictions of these other worlds in 2007. In “Susannah”, an Italian landscape adorns a bowl full of cherries set in front of a young woman. One cherry is lifted from the bowl but held close to the figure’s chest. A bird sits on the edge, not looking down at the cherries in front of him, but up at the one withheld. The landscape on the bowl is like the cherry for the viewer, it draws us away from the current plane and tempts us with a glimpse into another world. In many of her pieces, Ronquillo’s subjects hold single objects. These objects seem less of a peace offering and more like bait to draw us closer. In 2008, through the inclusion of a miniature portrait in “The Miniature”, we see the first pictorial depiction of someone other than the main character. This keepsake is clutched close to the heart while a small dog comforts the sorrow of his master. It is with this painting that Ronquillo begins to more deeply explore the idea of her characters’ friendships and romances.

Ronquillo’s most recent body of work, Devotion, delves into this symbolism specifically though the mysterious and alluring world of the Lovers’ Eye. Originating in the 1700’s, Lovers’ Eyes are Georgian miniatures depicting the eye of a loved one. These were usually commissioned watercolors on ivory with richly decorated frames and worn as jewelry. The first eye is thought to have been sent by the Prince of Wales to the widow Maria Fitzherbert. The court frowned upon their romance, so to maintain decorum, the prince sent Maria a portrait of only his eye. Lovers’ Eyes became fashionable shortly thereafter, when the couple married despite royal opinion. It is said when George IV became king, he wore Maria’s eye under his lapel. Inspired by this mystery and romance, Ronquillo moves beyond the sentimental miniature portrait. A glimpse of an eye, an eyebrow, a tear, a lock of hair does not suffice, but rather urges us to wonder: What is the nature of their relationship? Is the eye representative of a forbidden love, a child lost, a spouse? The surreal aspect of an isolated eye attracts Ronquillo; she says, “It is an idea of physical dismemberment which is symbolic of a removal or estrangement of a loved one. For anyone who’s ever been in love or had a crush on someone, the photograph of the beloved is treasured. So these are portable remembrances before the camera so to speak.”

The dress of her characters also points toward estrangement and danger. Many of the eyes are held by uniformed or exotically dressed figures accompanied by wild animals staring out of the frame. Arrows pierce the skin near the keepsakes, externalizing the pain of a lost or ruined love. In “The Inconstant,” the pain depicted is not that of the main character but of a lover. High atop her head, affixed to a gold turban, a single tear falls from a green eye toward its pearl frame. The eye of another lover is pinned close to her heart. A langur sits almost menacingly in her lap. These signs of infidelity and faithlessness betray the subject’s round, innocent face. More subtly, in “The Treasured,” a young uniformed boy sits with one finger covering a Lovers’ Eye brooch. A shell, fire- red coral and a strand of pearls balance precariously nearby. His eyes are shy and his mouth is tight with reluctance. His cheeks are red with embarrassment. We can only suspect that this young voyager has been asked to share his love story. He is not willing. Perhaps he believes his heart is as unstable as the still life on the ledge and, strangely enough, we are satisfied with the mystery of his reluctance.

In addition to these intimate oils, Devotion also includes larger mixed media works that present multiple firsts for the artist. The transition from the many layers of oil paint lends the pieces a graphic, contemporary feel. Ronquillo uses acrylic and watercolor to focus on line and flat color. The largest pieceintheshow,“TheRunaways,”isabreakthrough piece. For the first time, her character is in motion. The larger format gave Ronquillo the room to move away from the seated portrait. No longer a tableau for the viewers gaze, the runaways seem to pause for only a second in order for us to wonder what they are up to. Ronquillo’s growth and ability to successfully traverse mediums is a testament to her skill and intelligence. Year after year, she continues to further fascinate us with windows into mysterious worlds, urging our imaginations to take hold.

American Arts Quarterly

Exhibition Review American Arts Quarterly Spring 2011, Volume 28, No. 2, pp. 52-55 View PDF

Fatima Ronquillo’s small, colorful idealized portraits, on view May 20-June 24, 2011, at Meyer East Gallery in Santa Fe, build on a very personal approach to tradition. Born in the Philippines, she emigrated as a child to San Antonio, Texas, and now maintains a studio in Santa Fe. Ronquillo is a self-taught artist, who filters classic European portrait conventions through her own imagination. The resulting works have an apparent naiveté that lightly veils the formal eloquence of her compositions. Like the best Latin American artists of the colonial era, she translates elements of the European grand style into her own more modest yet pictorially vibrant idiom. Ronquillo titles her exhibition “Recuerdos,” using the Spanish word for keepsakes, emblems and mementos. The artist sees her portraits as “memory clues,” a response to the human “need for stillness and nostalgia.” The more familiar Spanish word for portraits is retratos, and Ronquillo may be signaling that her subjects are not so much individuals, whose faces have been shaped by their psychological history, as types of innocence or beauty.The features of her dramatis personae are highly stylized: her characters are all pale-skinned, with tiny mouths, delicate brows and soulful eyes. These are not religious paintings, yet they have a marked devotional aspect. The Spanish and Portuguese carried with them religious images, devotional “portraits” of Christ, the Virgin and the saints, that had enormous influence on indigenous artists, in their secular as well as their sacred work. Ronquillo adds details to her portraits that add a symbolic charge, like the attributes of saints. The same principle may apply in the society portrait, where the sitter wears the marks of office or is surrounded by meaningful objects—the soldier’s sword, the scholar’s books. Still, the biographical narrative is kept at a distance.

For Ronquillo, whose subjects are fantasy characters from the art historical past, the world she conjures is even more remote from immediate experience, yet it is convincing on its own terms. Her compositional formula is simple: a bust-length figure—dressed in a style vaguely reminiscent of the society-portrait past, any time from the Rennaisance through the nineteenth century—is posed in the foreground. Sometimes the figure is posed just behind a stone ledge, a convention familiar in images of Renaissance madonnas and princesses. Often, a smoothly idyllic landscape forms the backdrop.

The smallest of the paintings, Valentine (all works 2011), is 8-by-6 inches and would fit comfortably in your hand. The format builds on both the miniature portrait painting and the photographic carte-de-visite. A boy in a high collared jacket holds a folded billet doux, decorated with a red heart. Whether he is the sender, the recipient or an Eros dressed as a Mozartian page remains a puzzle, but the image is charming. The implications of the document in A Long List of Offenses are more troublesome, yet the child who holds the accusatory paper seems stoic. The crisp white of the list is pleasing against his bright red military-style jacket with blue piping and collar. Ronquillo’s images of children avoid sentimentality, both because she presents them in quasi-adult costumes and because she captures an aura of solemnity that reminds us how seriously children regard the daily slights of life. Goya’s portraits of slightly stiff yet poignant miniature adults come to mind. While there is a doll-like quality to Ronquillo’s subjects, their demeanor is restrained, melancholy. Their faces seem haunted by emotions past, rather than blank. A good example is Recuerdo (10-by-8 inches), in which a young woman holds a spray of lily of the valley in her slender fingers. A red-headed bird lies on the ledge in front of her, and an aura of regret prevails. The artist’s rich color palette—especially in the golden yellow of the girl’s dress and the embossed deep-blue-on-blue backdrop—works in robust tension with the wistfulness of the girl’s mood.

A group of more elaborate compositions feature glamorous women in surroundings replete with old master trappings. Ronquillo simultaneously calls attention to and transforms the historical conventions of the society beauty. The landscape backdrop in old master portraits is always, to some extent, a fiction, however illusionistically convincing it may be. The sitter and the countryside or town in the background do not occupy the same continuous space. Ronquillo’s dreamy landscapes acknowledge that artificiality. In Lady with Still Life (20-by-16 inches), the convention becomes a conceit, as the landscape is shifted from the background to the decoration on a bowl perched on the fore-ground ledge. The bowl is filled with fruit, including cherries that spill over the edge, attracting the attention of a snail. The artist’s bold colors are less blended and more localized than those used by the old masters. A lack of shadows underlines the flatness of the shapes. Here, the Titian-red hair of the woman plays off against the green of her shawl and background wall. The Letter (10-by-8 inches) could be a tribute to Vermeer. The lady wears a pearl earring and a loose red turban, and her dress is lemony gold, although more daringly low-cut than a woman would wear in a Vermeer scene. Old master opulence and private symbolism come together in Lady with Finch, Nest and Tulips (20-by-16 inches). The woman seated before the hazy landscape wears a bright gold dress and deep blue shawl. On the parapet before her is a showy still life of red-and-white-steaked tulips and a nest with three eggs. The nest is tilted up almost flush to the picture plane. A broken egg with an intense yellow yolk lies beside the nest. It’s Ronquillo’s version of the vanitas genre, a tribute to both beauty and transience. Such a still life would have had a clear meaning for a seventeenth-century Dutch artist and his audience. For Ronquillo, estrangement from transparent communal understanding is not necessarily a bad thing. “Whether the viewer gets the same story or symbolism behind a painting is not important,” she says. “I believe that the two separate acts of creating and looking at art elicit emotional, visceral responses. There is something magical, mysterious and intimate about that.” These jewel-like paintings intuitively fuse different aesthetic traditions, folk art and old master, with natural grace and an uncanny quality that may be a species of magic.

You must be logged in to post a comment.